Lamborghini Miura, Claude Monet: “Impression, soleil levant”

by Mrs Miura

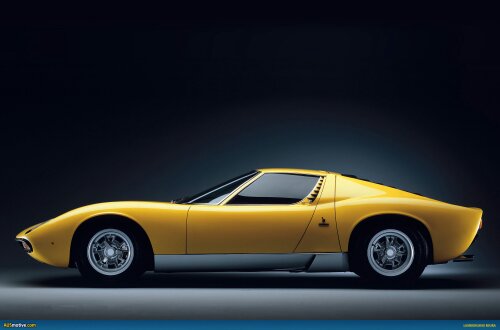

At the 1965 Turin Motor Show, the object that generates the greatest interest is the prototype PT400 (composed only of the chassis and mechanical) of the new Lamborghini which is not yet known who will be given the task of designing the body.

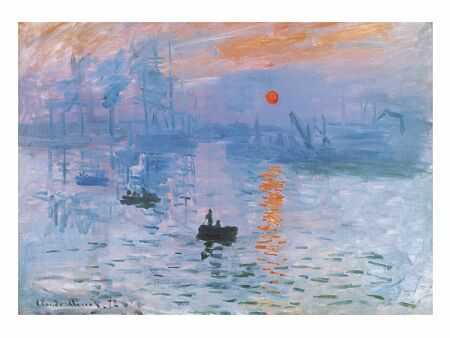

At the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874 the painting “Impression, Soleil Levant” by Claude Monet encodes the term “Impressionism”, which, from a journalistically ironic and derogatory term, becomes the definition of the perhaps most important movement in the history of figurative art, the first real challenge to the until then prevailing classicism and the dozer to all the vanguards of the Twentieth century.

The Miura comes from a steel monocoque with lightening holes, and even if the V-12 engine of 60 degrees, 3.929 cc and 350 hp comes from the one (though frount-mounted) of the 400 Gt, the founder of the family, it has the pure freshness of true novelties, not only objects intended to leave a mark, but also to open a road that will be traveled extensively by those who will come later.

And, in fact, just to stay at Lamborghini, this at the time absolutely new formula (the centrally mounted engine) is still gloriously at the base of the new Aventador, the first, however, after more than forty years, to abandon the 12 cylinder of the 400, the Miura, the Countach, the Diablo and the Murciélago.

It is drawn by the twenty-five years-old Marcello Gandini, at the Carrozzeria Bertone, and he develops the project together with the peers Bob Wallace, Gianpaolo Dallara and Paolo Stanzani.

The project, at least in its first embodiment, is not free from the flaws of youth, partially corrected in its latest developments, the SV version of 1971, like the placement of the gearbox, clutch and differential gear group inside the engine block, exposing the gearbox to dangerous overheating.

However, the Miura knows how to be forgiven its faults, with unprecedented performance (with its 280 km/h is, at its birth, the fastest production car in the world), but above all with an unmatched beauty. In its line of rare efficacy the stylistic innovations follow each other in an harmony of forms never seen before.

Featuring famous “eyelashes” on the headlights (born to make more appealing a particular otherwise taken by a simple Fiat), “Veneziane” blinds covering the engine, a rear grid where the octagon pattern is the signature of Gandini (which the new Aventador makes more than a tribute), and with a “double curve” profile that makes it so similar to a feminine silhouette, the Miura is a symphony of details that combine to make it not only beautiful, but also absolutely revolutionary. It’s low, wide, soft, and although not perfect, is a milestone in the car history.

“Impression, soleil levant” is the painting that conventionally represents the birth of the Impressionist movement, encoding those characters that will be all common to the group, although declined by each artist in an absolutely personal way. The visual arts overcomes the academic mythology representations of the Salon to focus finally on feelings to return to the observer.

Strokes are now free, vague, sometime even confused, rather than clearly defining what may be a sunrise or a sunset, leave the task of feeling sensations to the observer, working as an intermediary between the memory already belonging to the viewer and a new perception of the world, an impression that fluctuates between dreaming touches of color that are absolutely foreign to the figurative tradition for their unreality.

As the Miura’s “pop” colors are unprecedented in the automotive world (and they will be thereafter called “green Miura” and “orange Lamborghini”), so the soft and dreamy colors of Monet’s painting depart far from any desire of a faithful representation of real, defining the overcoming of the classical figurative objectivity to one, at that time, revolutionary concept of subjective interpretation of the reality, which results in exceeding the drawing and perspective for a particular chromatic expressiveness able to render on canvas not the objective reality, but the reality as it’s lived and felt by the artist, capturing the essential elements rapidly and not in an analytical way, giving precisely the impression.

The pure design of the Miura underwent a slight change with the birth in 1971 of the Spinto Veloce version, which makes necessary an enlargement of the engine bonnet, of the beautiful wheelarches (by design of semi-elliptic shape and not simply semi-circular) and the rear wheel track, and sees the disappearance of the “eyelashes” and the rear air intake with the octagon pattern, with other small cosmetic changes.

However, that doesn’t alterate the design.

If Ferruccio Lamborghini’s masterpiece is born as a bad-tempered answer to a long wait outside Enzo Ferrari’s door, the Monet’s one follows centuries of supposed realism that left no spaces for the artist’s inner feelings.

Both represent a point of final destination, and the birth of something new.

The Miura has been produced in 765 examples from 1966 to 1972, in three versions: P400, P400 S and SV, together with an unique Miura Roadster and some examples of Miura Jota, version developed for tracks which however has never take part in races for the reluctance of Ferruccio Lamborghini to the world of motor racing.

The Miura appears also in the 1969 movie “The Italian Job”.

“Impression, soleil levant”, oil on canvas, 43×63 cm, painted in 1973 is now in Paris, at the Musée Marmottan.

***

Al salone dell’Auto di Torino del 1965 l’oggetto che genera più scalpore è il prototipo PT400 (composto solo da telaio e meccanica) della nuova Lamborghini di cui ancora non si conosce la veste.

Alla prima mostra impressionista del 1874 la tela “Impression, Soleil levant” di Claude Monet codifica il termine “impressionismo”, che da un’espressione giornalisticamente ironica e dispregiativa, diviene la definizione del movimento forse più importante della storia dell’arte figurativa, la prima vera contestazione al classicismo fino allora imperante e battistrada a tutte le avanguardie del Novecento.

La Miura nasce da un’innovativa monoscocca d’acciaio piena di fori d’alleggerimento, ed anche se il motore 12 cilindri a V di 60 gradi da 3,929 cc e 350 cavalli deriva da quello (montato però anteriormente) della capostipite 400 Gt, ha la pura freschezza delle novità assolute, degli oggetti destinati non solo a lasciare un segno, ma anche ad aprire una strada che verrà ampiamente percorsa da chi verrà poi.

Ed infatti, solo per restare in casa Lamborghini, la allora nuovissima formula longitudinale posteriore è ancora gloriosamente alla base della nuova Aventador, la prima comunque, dopo più di quarant’anni, ad abbandonare il 12 cilindri della 400, della Miura, della Countach, della Diablo e della Murciélago.

È il venticinquenne Marcello Gandini a disegnarla, alla Carrozzeria Bertone, ed a svilupparla insieme ai pressoché coetanei Bob Wallace, Gianpaolo Dallara e Paolo Stanzani.

Il progetto, perlomeno nella sua prima realizzazione, non è esente da pecche di gioventù, parzialmente corrette nell’ultima evoluzione, la versione SV del 1971, come il collocamento del gruppo cambio, frizione e differenziale all’interno del blocco motore, soluzione che esponeva il cambio a pericolosi surriscaldamenti.

Tuttavia, la Miura sa far perdonare i propri difetti con prestazioni inedite (coi suoi 280 km/h è, alla sua nascita, l’automobile di serie più veloce del mondo), ma soprattutto con una bellezza senza pari. Nella sua linea di rara efficacia le innovazioni stilistiche si susseguono in un’armonia di forme mai vista prima.

Dotata di famosissime “ciglia” sui fari anteriori (nate per movimentare un particolare altrimenti ripreso da una semplice Fiat), di “veneziane” che coprono il motore, d’una griglia posteriore dal motivo ad ottagoni che è la firma di Gandini (e cui la nuova Aventador rende più d’un tributo), e con un profilo “a doppia curva” che la rende così simile ad una silhouette femminile, la Miura è una sinfonia di dettagli che concorrono a renderla non solo bellissima, ma anche assolutamente rivoluzionaria. È bassa, larga, morbida, e sebbene non sia perfetta, è una pietra miliare della storia dell’automobile.

“Impression, soleil levant” è il quadro che convenzionalmente rappresenta la nascita del movimento impressionista, codificando quei caratteri che saranno poi comuni a tutto il gruppo, seppur declinati da ogni pittore in maniera assolutamente personale.

L’arte figurativa supera le accademiche rappresentazioni mitologiche dei Salon per concentrarsi finalmente sulle sensazioni da restituire.

Le pennellate sono ora libere, vaghe, a punti perfino confuse, più che definire in modo netto quella che può essere un’alba od un tramonto lasciano all’osservatore il compito di provare sensazioni, proponendosi come tramite fra il ricordo già appartenente a chi guarda ed una nuova percezione del mondo, un’impressione (appunto) sognante che fluttua fra tocchi di colore assolutamente estranei alla tradizione figurativa per la loro irrealtà.

Come i colori “pop” della Miura non hanno precedenti nel

mondo dell’automobile (e verranno per questo da allora in poi chiamati “verde Miura” e “arancione Lamborghini”), così i colori morbidi e sognanti del quadro di Monet si allontanano decisamente da ogni volontà di fedele rappresentazione del reale, definendo il superamento della fedele oggettività figurativa secondo gli schemi classici da sempre adottati per un, all’epoca, rivoluzionario concetto di interpretazione soggettiva della realtà, che si traduce nel superamento del disegno e della prospettiva a favore soprattutto di una espressività cromatica capace di rendere sulla tela non la realtà oggettiva, ma quella immediatamente vissuta e sentita dall’artista, cogliendone rapidamente gli elementi essenziali e non analitici, appunto l’impressione.

Il puro design della Miura subisce un lieve cambiamento con la nascita nel 1971 della versione Spinto Veloce, che rende necessario un allargamento del cofano motore, e quindi degli splendidi passaruota (dal disegno semiellittico e non semicircolare) e della carreggiata posteriore, e vede la scomparsa delle “ciglia” e della presa d’aria posteriore dal motivo ad esagoni, oltre ad altre piccole modifiche estetiche che comunque non ne alterano il disegno.

Se il capolavoro di Ferruccio Lamborghini nasce come sanguigna risposta ad una lunga anticamera davanti alla porta di Enzo Ferrari, quello di Monet segue secoli di preteso realismo che non lasciava spazi al mondo delle sensazioni interiori dell’artista.

Entrambi rappresentano un punto d’arrivo definitivo, e la nascita di qualcosa di assolutamente nuovo.

La Miura è stata prodotta in 765 esemplari dal 1966 al 1972, in tre versioni: P400, P400 S e P400 SV, più un esemplare unico di Miura Roadster ed alcuni esemplari di Miura Jota, versione messa a punto per un utilizzo sportivo mai concretizzatosi per la ritrosia di Ferruccio Lamborghini verso il mondo delle corse automobilistiche.

La Miura compare anche nel film “Un colpo all’italiana”, del 1969.

Il quadro “Impression, soleil levant” è un olio su tela di 43×63 cm dipinto nel 1973 ed ora conservato a Parigi, al Musée Marmottan.

this is my comments ! thx for all !