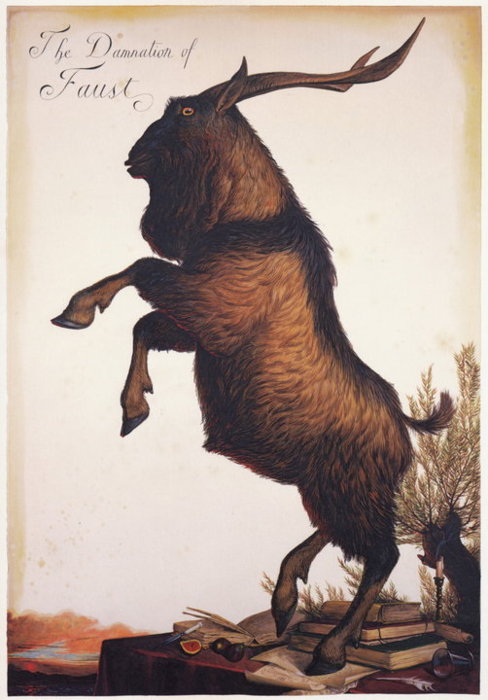

Fiat Mefistofele, Walton Ford “The Damnation of Faust”

“Please, allow me to introduce myself, I’m a man of wealth and taste. I’ve been around for a long long years, stole many man’s souls and faith”.

It isn’t always the three-headed monster of Dante or the goat of Goya and Walton Ford: the devil also knows how to take far more attractive forms, as the beautiful Gérard Philipe in “La Beauté du diable” by René Clair, who declaims with engaging voice its promises and not only tempts Faust with its unearthly (literally) and a little reckless elegance.

Or like the Fiat Mephistopheles.

It was born by accident in 1922 by a 14 years old Fiat SB4, whose engine explodes during a competition.

Is reduced to a wreck, a frame to be thrown away.

But not all successes born from perfection.

For example, Ernest Eldridge doesn’t look like an athlete and not even see well, by contrast is not short of courage: he wants to beat the land speed record, but a car is not enough: he needs a chimera. So he acquires the poor remnants of the SB4 and replaces the engine with that of a fighter-bomber, fatality, also a scrap leftover from the previous war.

It may surprise you, but between the two wars often reckless and daring pilots tried this kind of transplants, and several cars have survived enough to get to us. Moreover, the same series Bugatti Royale will donate its unused engines to some excellent locomotive, and many of the engines of the “three points racers” came from the automotive industry. They uses what is left from the war and they think it’s now unuseful: the Spitfires, the Merlins, but also Rolls Royce engines, and this FIAT A12 BIS.

It’s a huge six-cylinder engine huge that weights half a ton, 21,706 cc of displacement with 300 HP.

But for Elridge isn’t yet enough, and processes it by giving it four valves per cylinder which provide 20 more HP; at this point he needs to extend the frame that is 400 mm too short, and he tackles with parts salvaged from a London bus.

The Mephistopheles is therefore a monster of wood and aluminum which receives the baptism of fire on the dirt track (!) of Arpajon, France, in July 1924. It’s essentially an undriveable car, due to its composite nature, with the huge engine scalping to transmit (with two rear chains) the power to a rear axle that does what it can to remain on course, skating and wincing.

But are the noise and smoke that for wich most likely you will remember her: if the goat usually appears in a sulfur cloud, the rattling Mephistopheles runs in a hell of thick and sticky blue smoke. The FIAT yells, screams, buzzes, cackles in a defeaning metallic noise made by a continuous series of explosions which is a glorification of the internal combustion engine, eating gasoline and losing freely the lubricating oil.

Yet it is beautiful in its way. It is an infernal object put together in an imaginative way by an eccentric, but he can not attract. From the large radiator in shape of a truncated cone with the polished brass frame to the large tachometer, up to details that betray extreme care that no one would expect from a car designed to express a few seconds of pure speed, all suggests the warm beauty of old days, when nothing was left to chance.

But the melancholic nostalgia lasts only a moment, and once turned on, is the same Mephistopheles to wipe it out: emits an absolutely stunning amount of smoke, and vanishes in its own cloud of cooked oil, spitting flames from the single exhaust and roaring like no other.

Eldridge passed two times the records, the first (236 km/h) was not approved because the car wasn’t equipped with the reverse gear, then in some way, a week later, he was able to move it back in front of the judges (the car has still no reverse) and at last saw approved his new record of 235 km/h (which lasted a month, as usually happened), that remains the last obtained on a road regularly open.

Walton Ford has less imagination than Sir Elridge, and presents the devil as the usual goat, which reared up on two legs, staring at us sideways with a small yellow eye. His hooves rest on sheets and books, recalling of course the studies of Faust, its salvation and damnation.

Yet, in light of the common thread that links the works of Ford, this devil takes on another connotation.

If his watercolors usually hit us, disturbing us too, with scenes that highlight the substantial cruel nature of all beings, and even more Man, we can interpret this representation as a mirror.

So, therefore, we are the real devil, we are those who hunt the panther, who lock an eagle in a cage thinking about how to kill her, who kill the bear and her cubs causing far more destruction than them.

Ford reminds us that if “the civilization of a people is measured in how they treat animals”, we are the real Satan, and it’s Faust himself who creates its own corruption, desiring it.

Leopardi’s stepmother Nature is revealed in all its power, improperly becoming incarnate in an animal, when it’s already tangible in human form. The work of Ford subtly encourages us to reflect on the great plagues of society, the colonialism, the evil that comes from ignorance, the moral corruption inherent in the human.

And he opposes a nature that would be a triumph of hair, feathers, beaks, legs, beautiful silhouettes (though also affected by the inevitable wickedness of existence) which the man fatally tries to kill directly, perhaps for the futile purpose of representation, or which he kills as a result of the continued destruction of the Earth.

Marlowe’s Faust turns to Satan to get new ideas, new knowledge, new pleasures, and gets Mephistopheles at its own service in exchange for his soul, yet can not even use the new gifts the wicked deal brought him, but makes only meanness, reflecting its basically evil nature.

Come at the end of its days, he doesn’t knows true regret, even understanding what he has done (yes, he could finally possess -strictly speaking- the Knowledge, but he has lost the only thing that was worthy) he continues to implore an impossible stop of the time, and even begs for mercy to those who, Lucifer, can not have, because he’s only an extension of himself.

Lucifer is nothing but the evil that lurks within him, the devil in the mirror, the goat who stares at us.

“All beasts are happy, for, when they die, their souls are soon dissolv’d in elements”

Ford reminds us that the devil doesn’t dwells in the animal-goat, but in the animal-man, and urges us, not only through this watercolor, but with all his work, to silence the dark side and live in harmony, of course, respecting the Created.

The FIAT Mefistofele, originally black-painted, is at the Turin FIAT Museum. Eldridge lost the sight in one eye because of an accident and then died in 1937, just days before its friend Eyston, whom he supported, surpassed the world record speed of 555 km/h.

“The Damnation of Faust”, watercolor, gouache, pencil and ink on paper, 189.2×130.5 cm, 2008.

***

“Please, allow me to introduce myself, I’m a man of wealth and taste. I’ve been around for a long long years, stole many man’s souls and faith”.

Non è sempre il mostro a tre teste di Dante o il caprone di Goya e Walton Ford: il diavolo sa prendere anche forme ben più seducenti, come lo splendido Gérard Philipe in “La beauté du diable” di René Clair, che declama con voce seducente le proprie promesse e non tenta solo Faust con la propria ultraterrena (letteralmente) ed un po’ scapestrata eleganza.

O come la Fiat Mefistofele.

Nasce per caso, nel 1922, da una FIAT SB4 già vecchia di 14 anni, il cui motore esplode durante una competizione.

È ridotta ad un rottame, un telaio da gettar via.

Ma non tutti i successi nascono dalla perfezione.

Per esempio Ernest Elridge non ha l’aspetto dell’atleta e non ci vede neanche bene, in compenso non gli manca il coraggio: vuole battere il record di velocità terrestre, ma un’automobile non è abbastanza: ci vuole una chimera. Così acquista i poveri resti della SB4 e sostituisce il motore con quello di un cacciabombardiere, fatalità, anch’esso un rottame residuato dalla guerra precedente.

Può sorprendere, ma spesso fra le due guerre piloti incoscienti e coraggiosi tentavano questo genere di trapianti, e diverse auto sono sopravvissute abbastanza da arrivare fino a noi. D’altronde la stessa serie Bugatti Royale donerà i motori inutilizzati a delle ottime motrici ferroviarie, e molti motori dei “racer a tre punti” sono di derivazione automobilistica. Si utilizza ciò che è rimasto dalla guerra e che ora si pensa non servirà più: gli Spitfire, i Merlin, ma anche propulsori Rolls Royce, e questo FIAT A12 BIS.

È un motore da sei cilindri in linea enorme e pesante mezza tonnellata, 21.706 cc di cilindrata che garantiscono 300 CV.

Ad Elridge però non basta, e lo elabora dotandolo di quattro valvole per cilindro che forniscono 20 CV in più; a questo punto bisogna allungare il telaio che è troppo corto di 400 mm, e si rimedia con parti recuperate da un bus di Londra.

La Mefistofele è dunque un mostro di legno ed alluminio che riceve il battesimo del fuoco sulla pista sterrata (!) di Arpajon, in Francia, nel luglio 1924. È un’auto sostanzialmente inguidabile proprio per la sua natura composita, con l’enorme motore che scalpita per trasmettere (con due catene posteriori) tutta la potenza ad un retrotreno che fa quel che può per tentare di rimanere in traiettoria, pattinando e sussultando.

Ma sono il rumore ed il fumo ciò che molto probabilmente ricorderete di lei: se solitamente il caprone appare in una nube di zolfo, la Mefistofele corre sferragliando in un inferno di fumo bluastro denso e vischioso. La FIAT strepita, grida, ronza, schiamazza in un frastuono metallico assordante composto da una serie di detonazioni continue che è una glorificazione del motore a scoppio, divorando benzina e perdendo liberamente l’olio lubrificante.

Eppure è bellissima, a suo modo. È un oggetto infernale messo insieme in modo fantasioso da un eccentrico, ma non può non attrarre. Dal grande radiatore a tronco di cono con la lucida cornice d’ottone al grande contagiri, fino a particolari che tradiscono una cura estrema che nessuno si aspetterebbe su un’automobile concepita per esprimersi in qualche secondo di velocità pura, tutto suggerisce la calda bellezza dei tempi andati, in cui nulla veniva lasciato al caso.

Ma la malinconica nostalgia dura un momento solo, e una volta accesa, è la stessa Mefistofele a spazzarla via: emette una quantità assolutamente spettacolare di fumo, e svanisce nella propria nube d’olio cotto, sputando fiamme dal singolo scarico ed rombando come nessun’altra.

Elridge superò due volte il record, la prima (236 km/h) non fu omologato perché l’auto non era dotata di retromarcia, quindi in qualche maniera, una settimana dopo, egli riuscì a farla muovere all’indietro davanti ai giudici (la vettura è ancora priva di retromarcia) e vide finalmente omologato il suo nuovo record, di 235 km/h (che durò un mese, come abitualmente succedeva) e che resta l’ultimo ottenuto su una strada regolarmente aperta.

Walton Ford ha meno fantasia di Sir Elridge, e ci presenta il diavolo come il solito caprone, che impennato su due zampe, ci fissa di sbieco con un piccolo occhio giallo. I suoi zoccoli appoggiano su fogli e libri, richiamando ovviamente gli studi di Faust, sua salvezza e dannazione.

Eppure, alla luce del fil rouge che lega le opere di Ford, questo diavolo assume un’altra connotazione.

Se i suoi acquerelli di solito ci colpiscono disturbandoci con scene che sottolineano la sostanziale natura crudele di tutti gli esseri, ed ancor di più dell’Uomo, possiamo interpretare questa rappresentazione come uno specchio.

Siamo dunque noi il vero diavolo, siamo noi che diamo la caccia alla pantera, rinchiudiamo in una gabbia l’aquila pensando a come ucciderla, siamo noi che uccidiamo l’orsa ed i suoi cuccioli provocando ben più devastazione di loro.

Ford ci ricorda che se “la civiltà di un popolo si misura nel modo in cui tratta gli animali”, Satana non siamo altri che noi, ed è Faust stesso a creare la propria corruzione, desiderandola.

La Natura matrigna di Leopardi si palesa in tutta la sua potenza, incarnandosi impropriamente in un animale, quando invece è già tangibile in sembianze umane. L’opera di Ford ci stimola sottilmente a riflettere sulle grandi piaghe della società, il colonialismo, la cattiveria che deriva dall’ignoranza, la corruzione morale insita nell’essere umano.

E contrappone una natura che sarebbe un trionfo di peli, piume, becchi, zampe, silhouette bellissime (seppure anch’esse toccate dall’inevitabile malvagità dell’esistenza) che fatalmente l’uomo tenta di uccidere direttamente, magari per lo scopo futile di consegnarne la rappresentazione, o che uccide come risultato della continua distruzione della Terra.

Il Faust di Marlowe si rivolge a Satana per avere nuovi stimoli, nuova conoscenza, nuovi piaceri, e riceve Mefistofele al proprio servizio in cambio dell’anima, eppure non riesce nemmeno a sfruttare i nuovi doni che il patto scellerato gli ha portato, ma commette soltanto bassezze, a riprova della sua natura fondamentalmente malvagia.

Giunto alla fine dei suoi giorni, non sa neanche pentirsi davvero, pur capendo ciò che ha fatto (ha sì potuto finalmente possedere -in senso stretto- la Conoscenza, però ha perso l’unica cosa che avesse valore), ma continua ad implorare un, impossibile, fermarsi del tempo, e addirittura chiede pietà a chi, Lucifero, non può averne, in quanto è soltanto un’estensione di egli stesso.

Lucifero non è altro che il male che cova dentro di lui, il diavolo allo specchio, il caprone che ci fissa.

“Felici gli animali, perché morendo cedono l’anima agli elementi”.

Ford ci ricorda che il diavolo non alberga nell’animale-caprone, ma nell’animale-uomo, e ci esorta, attraverso non solo questo acquerello, ma tutta la sua produzione, a mettere a tacere il lato oscuro e vivere in armonia, naturalmente, rispettando il creato.

La FIAT Mefistofele, in origine nera, si trova al Museo FIAT di Torino. Elridge perse la vista da un occhio a causa di un incidente e morì poi nel 1937, pochi giorni prima che l’amico Eyston, da lui supportato, superasse il record mondiale di velocità a 555 km/h.

“The Damnation of Faust” è un acquerello, gouache, matita e inchiostro su carta di 189.2×130.5 cm realizzato nel 2008.